By Maria Schweer-Collins, PhD, Research Assistant Professor, HEDCO Institute for Evidence-Based Educational Practice

Artificial intelligence (AI) shows up regularly in our lives, and in many ways, has made the ‘everyday’ of life a little bit easier. AI helps you purchase things with just your face and a smartphone, recommends new music that ‘fits’ with the tunes you have been playing on repeat, keeps your email “cleaner” by filtering out spam and other unwanted messages, and even breaks down communication barriers by offering translation of visual images from one language to another. Importantly, AI is moving past simply making our lives easier and more convenient, with tools that humans can now use to assist with decision making. The conversation around the benefits, drawbacks, and ethics of AI-decision making has gained widespread attention with the public release of AI chatbots, those AI-fueled resources that can respond to you with human language.

Are we ready for AI-assisted decision making in education?

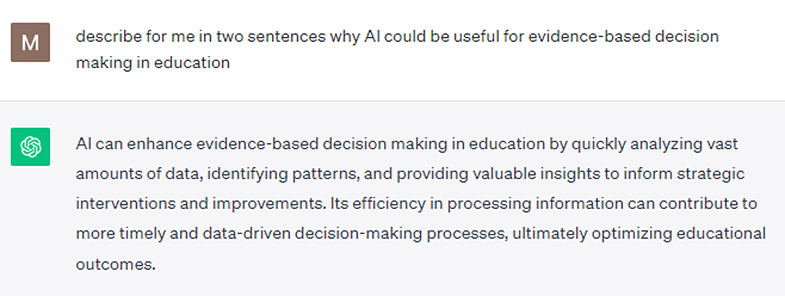

So, are humans ready to use AI to help us with evidence-based decision making in the K-12 education space? And is AI technology ready to assist us? As I sat down to write this post on the potential benefits and limitations of artificial intelligence (AI) for evidence-based educational decision making, the thought occurred to me that AI itself might have some thoughts about this. Below is my conversation with AI that followed, with “M” being the human (me) and the green symbol being ChatGPT.

Admittedly, this is a strong response from ChatGPT. There are many barriers to getting data into the hands of educators. Research on effective programs and practices is often unavailable to educators, requiring paid subscriptions, or findings are simply not published or shared out for several years after the research is completed. This, together with the sheer volume of data and research that exists, makes the ability of AI to rapidly analyze research from thousands of articles and generate practical recommendations for busy educators (something researchers haven’t historically prioritized) a huge win for all.

This answer from AI also echoes several of our values at the HEDCO Institute, most significant, the need of educators to have research that can be used to aid in evidence-based decision-making process when decisions are being made. In fact, it is the greater responsiveness of research findings to current issues in education that have the greatest potential to impact outcomes for K-12 students.

Now, before you close your browser and leave with only the amazing potential of AI in mind, stick around for a few minutes longer.

What are the limitations of AI-assisted decision making in K-12 education?

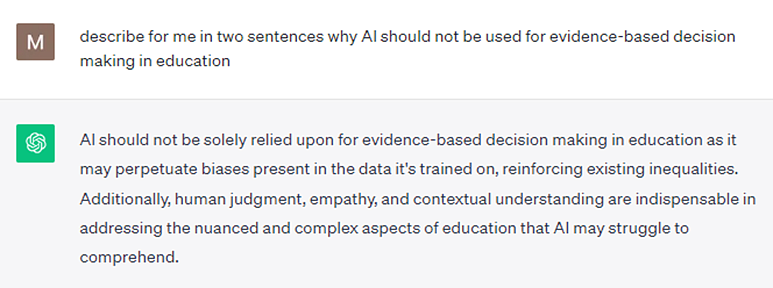

Many educational researchers and practitioners have also voiced valid hesitations about AI for decision making. In my curiosity, I wondered if AI could identify the same challenges with its own potential issues that I want to highlight today. Here is what Chat GPT had to say about the potential drawbacks of AI for evidence-based educational decision making.

Okay, okay, I suppose AI did set me up well to discuss the limitations. What are those?

AI has several significant challenges that impede the potential utility of AI decision-making. Some of the notable challenges are unreliability, perpetuating biases in the underlying data it synthesizes, and difficulty handling conflicting data. There are numerous other concerns about direct impacts on students, for example, how students’ unregulated use of AI will impact their own learning. I won’t focus on those student-focused concerns today but do want to point out that there are many facets of concern for the risks of AI in education, and the ethical uses of AI, all of which warrant careful attention.

Challenges in the use of AI for education decision-making

Challenge | Implication |

|---|---|

Reliability, Transparency, and Replicability | AI has the tendency to provide unreliable results. What do I mean by unreliable? If AI searches through millions of words and thousands of research articles and doesn’t find a sufficient response, it may create one from whichever sources it reviewed. Some of this has to do with how chatbots are trained to process language (i.e., the text included in the database, which may be research articles, blogs, webpages, proprietary information, or a combination of all of these and the “randomness” that is programmed into chatbots to improve the human quality of their responding) and the ability of the chatbot to use that same training for a new subject or question you might ask. How could this impact education? Imagine if only one research study exists on the topic of an English Language Learner intervention for kindergarten students. AI might generalize the findings from that study and even recommend the implementation of such a program, even if the results within that study were mixed/inconclusive. Because many AI chatbots are proprietary there is a lack of access to the algorithmic code and databases that underlie the chatbots’ functionality. This lack of transparency makes it hard to assess the rigor, bias, and safety of chatbot outputs or replicate answers generated by chatbots. Without human checks, AI therefore has potential to generate misinformation about what is effective in education. |

Perpetuating Bias | Education stakeholders and researchers are acutely aware of the many biases present in research, biases due to the limits of the sample representativeness (e.g., only boys, or majority white students, only public schools in a single geographic region), due to the way the study was conducted (e.g., a convenience and non-random sample of students, no comparison group), or due to the incomplete reporting of results. Currently, AI tools don’t clearly account for such biases in the recommendations or answers they provide to educators, and even worse, if the answer the chatbot provides isn’t traceable to an accurate source, the bias will not be acknowledged at all, even by the human user. This has the potential to perpetuate practices that are not culturally sensitive or matched to the context or needs of a given school. Certainly, all research can perpetuate bias, but to acknowledge and address it, human critique and judgement is necessary. For example, at the HEDCO Institute, we address these biases in our systematic reviews by evaluating them with standardized tools and through evaluating the strength of evidence based on the study characteristics themselves. We look forward to the day when AI can also help us in addressing and appropriately documenting these biases. |

Identifying and Resolving Conflicting Evidence | One of the trickiest things for AI to sort through are sets of conflicting research findings. For any given educational intervention, it is possible for several studies to show positive effects and several studies to show null or negative effects. Although AI chatbots can be more reliable when there is true consensus on a topic, when mixed results show up, the amount of human verification needed increases. Verifying output from a chatbot is more difficult when the user is less familiar with the content or when the sources the chatbot uses are inaccurate. The average user who is approaching the chatbot with important and timely questions may have difficulty knowing whether a recommendation or answer is trustworthy or not. |

Following the future of AI in education

We should all stay tuned for how AI will impact the future of education research and education decision-making. Alongside our curious optimism (or understandable skepticism), we must cautiously move forward knowing that AI tools are likely here to stay. With each new step forward in AI development, we must ask about the risks and benefits, and balance our integration of AI into education with the wise counsel of human decision-making, as we have always done.

Are you interested in learning about recent applications of AI for educators?

Here are two education-focused AI chatbot tools in development that you track. These were also recently covered in The 74.

The Learning Agency’s chatbot

The Learning Agency is developing a chatbot (currently unnamed) that only analyzes research evidence archived in U.S. Department of Education’s “Doing What Works Library.” Although this is likely to improve the quality of evidence that the AI tool will synthesize, and the developers did find the prototype chatbot was more accurate than ChatGPT, they also report several limitations. Foremost is that this chatbot doesn’t know when it just doesn’t know the answer. Additionally, not all educational research is archived in this library, so it’s possible important and/or conflicting evidence is not being used in the AI-generated responses. This could lead to bias around programs or practices that are now dated, those that lack robust evidence, or a lack of evidence that shows effectiveness for student groups that have been historically marginalized due to race, gender, nationality, or socioeconomic status.

ISTE’s Stretch AI chatbot

The International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) just introduced a prototype AI chatbot, Stretch AI. This chatbot synthesizes peer-reviewed research that has been approved by the developers, which adds a layer of quality control. Stretch AI also cites the research it is synthesizing so end users can go to the source and get additional information or verify the synthesized recommendations and results. The developers are also working to ensure that Stretch AI can indicate when there isn’t enough information or research available to make a reliable recommendation, addressing another key limitation of AI chatbots. Stretch AI is up against the same challenge as the Learning Agency’s chatbot, namely that the results generated by the chatbots can be biased based on the research that is being reviewed.

HEDCO Institute Blog 6- October 26, 2023