by Melissa Mouthaan and José Manuel Torres, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

There’s broad agreement that education policies and practices should be informed by evidence. But making that happen in practice takes more than just having good research available. Evidence doesn’t speak for itself – it needs to be mobilized.

At the OECD, we understand knowledge mobilization to be any deliberate effort to make research more useful to policy and practice questions, and more widely used. This includes:

- Producing research that is highly relevant to policymakers and practitioners;

- Improving access to the research;

- Supporting educators and policymakers to engage with the research; and

- Building the conditions for evidence to inform decisions in meaningful ways.

In short: it's about helping research make an impact in education.

Embedding research use in education systems involves a range of professionals taking on a variety of activities; it is crucial these actors – and knowledge mobilization systems broadly – are well-supported to achieve their goals.

Who is doing what?

One key group is knowledge intermediaries. These are organizations – or departments within larger organizations – that play an essential role in helping policymakers and practitioners engage with research to inform their decisions and daily practices. Brokering research knowledge may be their main purpose, or they might take it on as part of a broader mission.

Knowledge intermediaries: organizations or departments within organizations that play an essential role in knowledge mobilization, enabling practitioners’ and policymakers’ engagement with research to support their practices and decision making.

To our knowledge, there has been little analysis of the characteristics and impact of intermediaries in the knowledge mobilization sphere in education. To address this gap, the OECD conducted a survey in 2023 that collected responses from 288 intermediary organizations across 34 countries. These included formal intermediaries (organizations with a formal mission to facilitate research use), as well as research institutes, public agencies, teacher education providers, funding bodies, unions, inspectorates, and consultancies – many of which play an important role in brokering research knowledge even when it isn’t an explicit or formal part of their mandate.

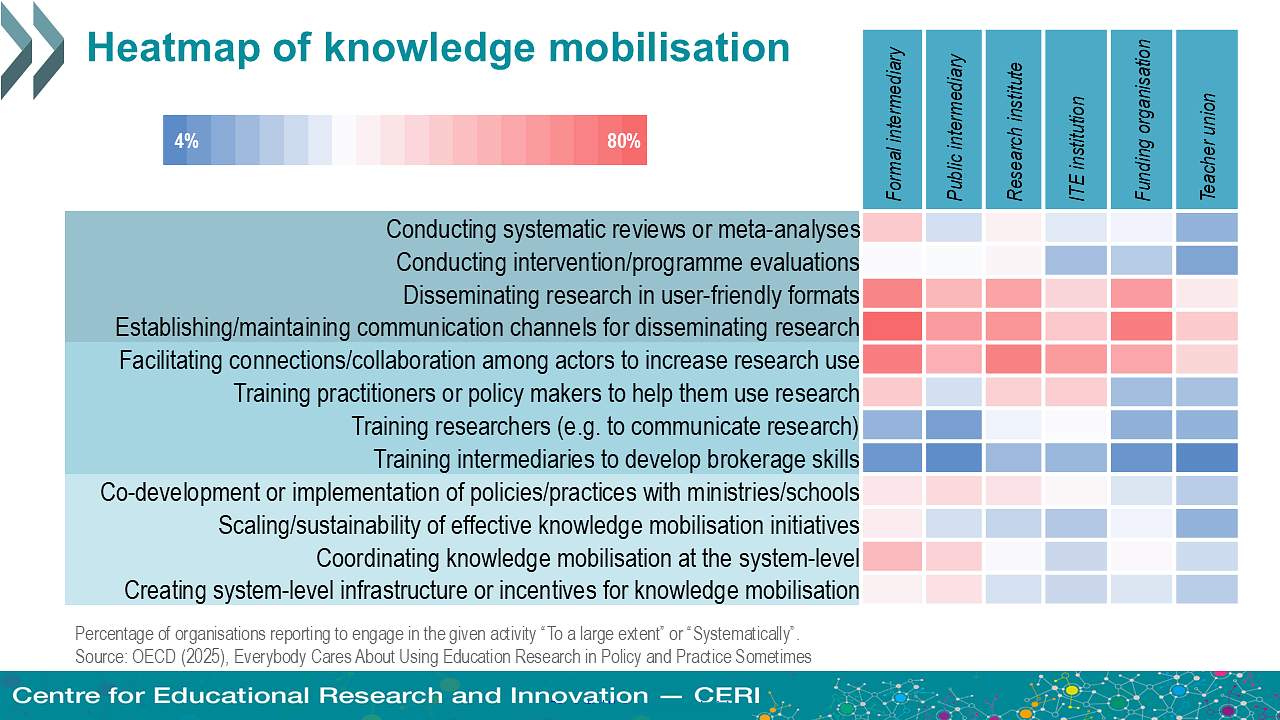

The heatmap below shows how engaged intermediaries are in different knowledge mobilization activities. Each cell indicates the percentage of each type of intermediary that said they engage "to a large extent" or "systematically" with the given activity.

Intermediaries are most active in sharing research and building partnerships, but are less involved in training or capacity-building.

Our analysis confirmed that researchers often lack support to improve how they communicate with policymakers or teachers. Intermediaries themselves also rarely receive training in how to broker knowledge effectively. This latter finding is also reflected in the systematic review of factors shaping research use in policy: education research studies were far less likely than studies in other knowledge domains – such as health, public administration, and sustainable development – to describe training or capacity-building activities in knowledge mobilization.

That said, there are strengths to build on. Two-thirds of intermediaries have channels for sharing research. Additionally, fostering collaboration and partnership building is a major activity, with one-third of intermediaries offering sustained and direct support to schools and policy organizations. This sustained support is more effective than one-off training sessions. Some also offer long-term support to schools or policy bodies – which tends to be more impactful than short-term projects or standalone reports.

There are also promising examples of infrastructure that have been set up to improve knowledge mobilization, including:

- A shift in government funding of education research in Germany has resulted in more research production that is considered empirical and applicable to policy makers’ needs.

- A research-policy nexus space established in a government department in South Africa, enabling exchanges between researchers, government officials, and other stakeholders.

Analyses of intermediary efforts to build these kinds of infrastructure give insight into what might work at the system level to support effective knowledge mobilization.

Who should be doing what in knowledge mobilization?

Not every organization needs to do everything. Indeed, for every actor to intensively undertake every type of knowledge mobilization activity in the heatmap would suggest a lack of cost-efficiency and coordination. What matters is that roles correspond to organizations’ profiles and capacity, and that the system as a whole is coherent.

Not every organization needs to do everything. What matters is that roles correspond to organizations’ profiles and capacity, and that the knowledge mobilization system as a whole is coherent.

Some countries, such as the Netherlands, have invested substantially in their ‘science-for-policy’ infrastructure, and now face the challenge of identifying how best to coordinate actors and activities. Initiatives that map the landscape of actors can help periodically identify active intermediaries and their contributions. This helps clarify who is best placed to do what — and where gaps or overlaps may exist.

Coordinating knowledge mobilization at the system level across different actors is reportedly done by more than one-third of the organizations that responded to the OECD survey. What do these organizations understand by ‘coordination’? Do they coordinate collectively (e.g., operate as a network) or are there parallel efforts? How many actors can – or should – coordinate knowledge mobilization at the same time, and who should those actors be? Answers to these questions will vary depending on the way education is governed in a system:

- In top-down, centralized systems, the national ministry might be the logical actor to coordinate knowledge mobilization.

- In decentralized systems, an independent body, such as a formal intermediary or some form of a network of organizations, might be better suited.

Overall, a better understanding of the diverse roles that different organizations play in knowledge mobilization can help to identify areas where additional support and coordination are needed to bridge the gap between research, policy. and practice.

Sources

This blog highlights findings from two data sources: The 2023 OECD Survey of Knowledge Mobilization in Education, and an external systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policy makers conducted in 2024 that included 85 studies in the education knowledge domain.

HEDCO Institute article 22 - July 13, 2025