by Joanna Hermida, Graduate Student, Patrick C. Kennedy, Senior Research Associate, Lillian Durán, Professor, Gina Biancarosa, Professor and Ann Swindells Chair in Education, Center on Teaching and Learning, University of Oregon

In 2024, twice as many 4th grade English Learners (ELs) read below basic level on the National Assessment of Educational Progress compared to students not designated as ELs (71% vs. 35%).1 Universal screening and effective reading intervention are promising approaches for reducing these discrepancies in reading outcomes,2 with educators in at least 80% of U.S. states conducting universal screening to support early identification of reading problems.3 However, typical practice in the U.S. is to screen for reading problems only in English and little guidance exists about how to interpret performance in multiple languages.4,5,6,7,8 Recent projects by our team of researchers at the University of Oregon (UO) highlight innovative dual language approaches to screening for bilingual learners.

Importance of bilingual screening for bilingual students

Bilingual learners who receive early intervention tailored to their needs are more likely to achieve reading success in both languages.9,10 A core challenge in providing tailored support is distinguishing between:

- students who are in the process of developing proficiency in English but who have adequate literacy skills in their first language, and

- those who demonstrate persistent challenges in literacy development that affect their ability to read in any language.11

Bilingual screening provides educators with a more complete understanding of multilingual students’ reading ability and positions them to support multilingual students' learning needs, reducing the risk of misidentification for special education services and leading to improved academic outcomes and more inclusive educational practices.12

Bilingual students have diverse skills across English and Spanish

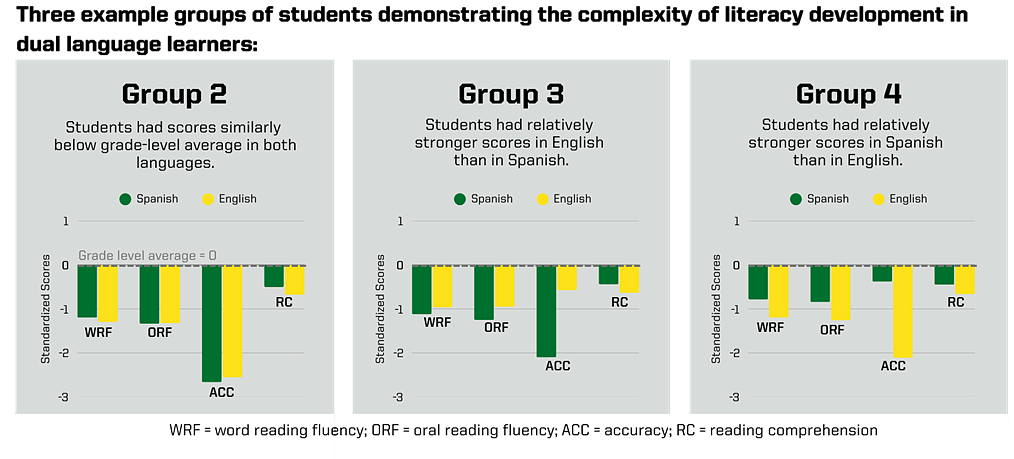

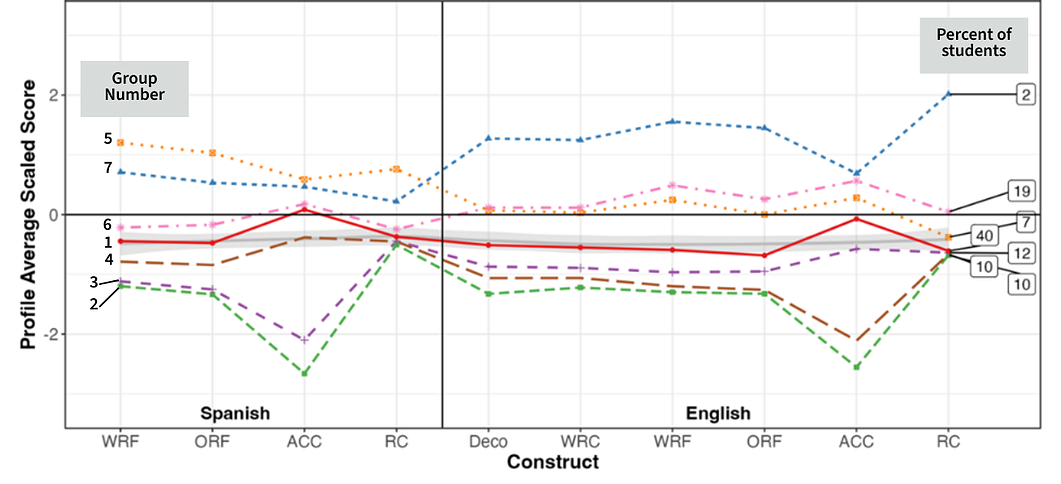

Our team’s recent latent profile analysis of beginning-of-year performance for second-graders on a range of literacy measures underscores the complexity of literacy development in Spanish-English bilingual learners. Latent profile analysis is a way to identify groups of students in a dataset who have similar patterns of outcomes. We identified seven distinct groups of students.

- Group 1, comprising the largest proportion of students (40%), performed near the sample mean in English and Spanish across all measures.

- In contrast, students in Groups 2 (10% of students), 3 (12% of students), and 4 (10% of students) all demonstrated below average performance across measures but differed in important ways. Students in Group 3 demonstrated relatively stronger reading accuracy in English than in Spanish, whereas students in Group 4 showed the opposite pattern, with relatively stronger Spanish accuracy and lower English accuracy, indicating relative strength in one language. Students in Group 2 had accuracy scores similarly below the mean in both languages, indicating a language-independent reading difficulty.

- Students in Groups 5 (7%), 6 (19%), and 7 (2%) showed progressively higher levels of literacy performance across both languages, with students in Group 7 demonstrating the highest average scores.

As these data clearly show, assessing these students in only one language would underestimate some students' reading abilities–potentially misidentifying language development as a reading disability. Effective multilingual assessment practices thus require assessments that differentiate between language acquisition challenges and true reading impairments, helping educators ensure that multilingual students receive the instructional support they need.13,14

Spotlight: California

Recently, California became the first state to formally recognize the importance of disentangling English proficiency from reading difficulties for multilingual students. In December 2024, the state approved four assessments for universal screening of reading difficulties in kindergarten through Grade 2, in response to legislation signed into law in July 2023 (SB 114, TK-12 Education Omnibus Trailer Bill).

As time goes on, hopefully more states will recognize the importance of accounting for the bilingual status of their student population to facilitate the accurate identification of multilingual students in need of reading intervention.

Example Screeners:

Multilingual assessment systems developed by UO faculty:

mCLASS with DIBELS 8th Edition and Lectura: DIBELS 8 is an English-language reading screener that was developed at the UO by researchers at the Center on Teaching and Learning, including Dr. Gina Biancarosa and Dr. Patrick Kennedy. Lectura is a Spanish-language reading screener that was developed in collaboration with UO faculty member Dr. Lillian Durán.

Multitudes: Multitudes is a new reading screener with English and Spanish subtests. Dr. Durán, along with Dr. Cengiz Zopluoglu, served in leadership roles on the development team for Multitudes.

Both systems offer bilingual screening that enables educators to distinguish the cross-linguistic strengths and weaknesses of the children being screened. Multitudes was normed with a population representative of California’s students, whereas DIBELS and Lectura were normed with nationally representative samples.

Full Latent Profile Analysis Results:

Note: This figure displays standardized scores (z-scores) for each literacy measure, where 0 represents the grade-level average, positive values indicate above-average performance, and negative values represent below-average performance. The shaded gray line represents the average across profiles. WRF = word reading fluency; ORF = oral reading fluency; ACC = accuracy; RC = reading comprehension; DECO = decoding; WRC = words read correctly.

HEDCO Institute article 20 - April 30, 2025

References

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2024a). NAEP data explorer. National Assessment of Educational Progress.

- Project ELITE, Project ESTRE2LLA, & Project REME. (2015). Effective practices for English learners: Brief 2, assessment and data-based decision-making. Washington, DC: U.S. Office of Special Education Programs.

- Dilbeck, L. (2023). More states are screening for dyslexia. We need a plan for what happens next. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2023-09-22-more-states-are-screening-for-dyslexia-we-need-a-plan-for-what-happens-next

- Neuman, S. B., Quintero, E., & Reist, K. (2023). Reading reform across America: A survey of state legislation. Albert Shanker Institute. Retrieved from https://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2023-07/ReadingReform%20ShankerInstitute%20FullReport%20072723.pdf

- EdWeek. (2023). Most states screen all kids for dyslexia. Why not California? https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/most-states-screen-all-kids-for-dyslexia-why-not-california/2023/03

- Linan-Thompson, S., Ortiz, A., & Cavazos, L. (2022). An examination of MTSS assessment and decision-making practices for English learners. School Psychology Review, 51(4), 484-497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2001690

- Ortiz, A. A., Robertson, P. M., & Wilkinson, C. Y. (2018). Language and literacy assessment record for English learners in bilingual education: A framework for instructional planning and decision-making. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 62(4), 250-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2018.1443423

- Vazquez, M., Laakman, A. L., Loria Garro, E. S., Tan, S. X. L., & Keller-Margulis, M. A. (2024). Curriculum-based measurement in languages other than English: A scoping review and call for research. Contemporary School Psychology, 28(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-023-00487-z

- Durán, L. K., Roseth, C., Hoffman, P., & Robertshaw, M. B. (2013). Spanish-speaking preschoolers’ early literacy development: A longitudinal experimental comparison of predominantly English and transitional bilingual education. Bilingual Research Journal, 36(1), 6-34. doi:10.1080/15235882.2012.735213

- Genesee, F., Paradis, J., & Crago, M. (2019). Dual language development and disorders: A handbook on bilingualism and second language learning. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

- Lesaux, N. K. (2012). Reading and reading instruction for children from low-income and non-English-speaking households. Future of Children, 22(2), 73-88.

- Lindholm-Leary, K. (2016). Bilingual and biliteracy development in dual language programs. Applied Psycholinguistics, 37(4), 713-734

- García, O., & Solís, A. (2020). Bilingual education and equity: A critical perspective. Multilingual Matters.

- Durán, L. K., & Pollard-Durodola, S. D. (2018). Bilingual language interventions for young dual language learners with disabilities