by Anthony Petrosino, Director, and Ericka Muñoz, Research Associate, WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center

Warning: The following article discusses school shootings, homicide, and youth violence. This content may be disturbing for some readers.

The September 4th shooting at Apalachee High School in Georgia that left two students and two teachers dead, and nine persons wounded, was the latest in a line of multiple casualty shootings at schools in the United States. Given the incredible suffering and loss of life resulting from these tragic events, they understandably generate considerable media attention and public concern over the safety of students and staff. Schools should be safe places for students and staff to come to each day without the threat of violence.

One of our jobs as researchers is to examine data to shed light on the issue and provide perspective. Despite the attention generated by the Apalachee High shooting as well as other high casualty school shootings (e.g., Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, Santa Fe, Uvalde), the data indicate something very surprising. For nearly 30 years --approximately 98-99% of all homicides of school-aged youth (generally youth between the ages of 5 and 18) occur outside of schools. One injury or death caused by violence in the school setting is already too much, but let’s dig into the data a bit more to get a better sense of what’s going on.

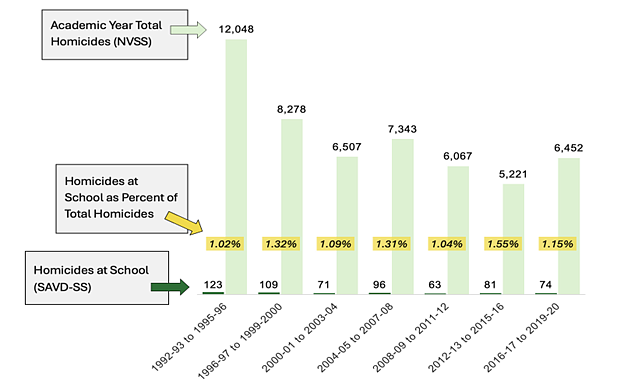

The Figure provides the total homicides on school grounds using the School Associated Violent Death Surveillance System (SAVD-SS) and the total number of homicides of school aged youth using the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS). These data are provided from academic year 1992-1993 to academic year 2019-2020, in four year increments (See below for more detail on these data).

As we can see in the Figure, school-related homicides have hovered between 1% and 2% of the total number of homicides of school-aged youth for these four-year increments. Even for periods in which high casualty events are included (such as in 1999, 2012 and 2018), the proportion of school-related homicides did not reach 2% of all homicides.

What should these data inspire us to do?

Yes, we absolutely must protect children—and staff—in school. Parents are entrusting their children to educators. In no way do we want to minimize the pain and suffering caused by a shooting such as what occurred at Apalachee High School. However, given that the vast majority of homicides of school-aged children do not occur in school—but in the home, on the streets, and at other venues—a comprehensive approach is needed. If we truly care about children, we’ve got to do a lot more.

For educators:

- advocate for effective, community-based approaches to help address factors contributing to youth violence in the home and neighborhood environments where the majority of these incidents occur.

- implement, within the schools, comprehensive approaches to student well-being and connectedness, incorporating effective emotional support, trauma-informed approaches, conflict resolution and other training and services. These supports can strengthen youth to cope in school, but more importantly, outside of the school environment.

For policymakers:

- balance the policy focus on school safety measures with appropriate investments in evidence-based social services, mental health support, and violence prevention programs that reach into the heart of our communities.

- inform policies with comprehensive data to guide policy use and evaluation to understand how they are faring in reality compared to their design and promise.

It is the rare educator, policymaker, parent, or police officer who doesn’t care about children. But while caring is necessary, it is insufficient. These data should provoke us to do more to protect children everywhere. Yes, that means in school. But just as importantly, we need to do more to protect them in their homes and the communities in which they live.

Selected Resources on School and Community Initiatives for Youth Violence Prevention

- Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development

- National Association of School Psychologists School Violence Prevention

- SchoolSafety.Gov Youth Violence Prevention

- World Health Organization School-based Violence Prevention

- Youth.Gov Violence Prevention

- US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Report on Indicators of School Safety, 2024

Data and Methods

We examined data that are routinely compiled by the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) for their periodic reports on school safety. Homicides and suicides that occurs on school grounds are tracked by the Center for Disease Control’s School-Associated Violent Death Surveillance System (SAVD-SS). The SAVD-SS not only tracks homicides and suicides that that occur in the school building during normal operating hours, but also those that might have taken place on the bus to and from school or at school events after hours (e.g., football games). The Center for Disease Control’s National Vital Statistics System (NVSS) allows NCES to identify the total number of homicides of school-aged youth. Comparing the SAVD-SS and NVSS data allows NCES, and us, to determine the proportion of homicides that occur on school grounds versus total homicides for school-aged youth.

Limitations

We acknowledge that these data do not tell us about any preceding factors that may have led to the homicide. For example, an altercation that occurred in school may have spilled over to a homicide that occurred later on the street. Thus, although the homicide would not be captured by the SAVD-SS, the school was very much related to what happened. Moreover, using 4-year increments allows us to simplify the table, but it masks individual year data. On a few occasions, homicides at school hit 2%-3% of total homicides for that year.

About the authors:

Anthony Petrosino serves as Director of the WestEd Justice and Prevention Research Center. He is also an Affiliated Faculty and Senior Research Fellow at George Mason University’s Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy.

Ericka Muñoz is a Research Associate at WestEd's Justice and Prevention Research Center and is currently pursuing graduate studies in the Criminology, Law & Society program at the University of California, Irvine. With a strong focus on data visualization, Ericka's work bridges the gap between data science and social science, making insights both informative and visually compelling.

HEDCO Institute Blog 15- Oct. 3, 2024