By Maria Schweer-Collins, PhD, Research Assistant Professor, HEDCO Institute for Evidence-Based Educational Practice

In May, the HEDCO institute released findings from our review on school-based anxiety prevention programs for K-12 students. The work continues our team’s focus on school-based mental health prevention research and builds from our first review of depression prevention programs.

This new review underscores the importance of addressing anxiety in childhood, as anxiety disorders are twice as prevalent in adolescent populations compared to depression. Recent estimates show that 1 in 5 youth experience clinically elevated anxiety symptoms, and anxiety and other behavioral disorders are among the leading causes of illness and disability among youth worldwide. We again review prevention programs delivered in schools, because the classroom is a setting where most children and adolescents can be reached.

What did we find?

Our review summarized evidence from 28 studies involving nearly 15,000 students. We found that anxiety prevention programs are likely to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms on average, but the effect is small. We also looked into whether anxiety prevention programs reduced anxiety diagnoses and improved student well-being outcomes. In these areas, the results were mixed – school-based anxiety prevention programs may or may not lead to improvements for students.

What types of studies were included in the review?

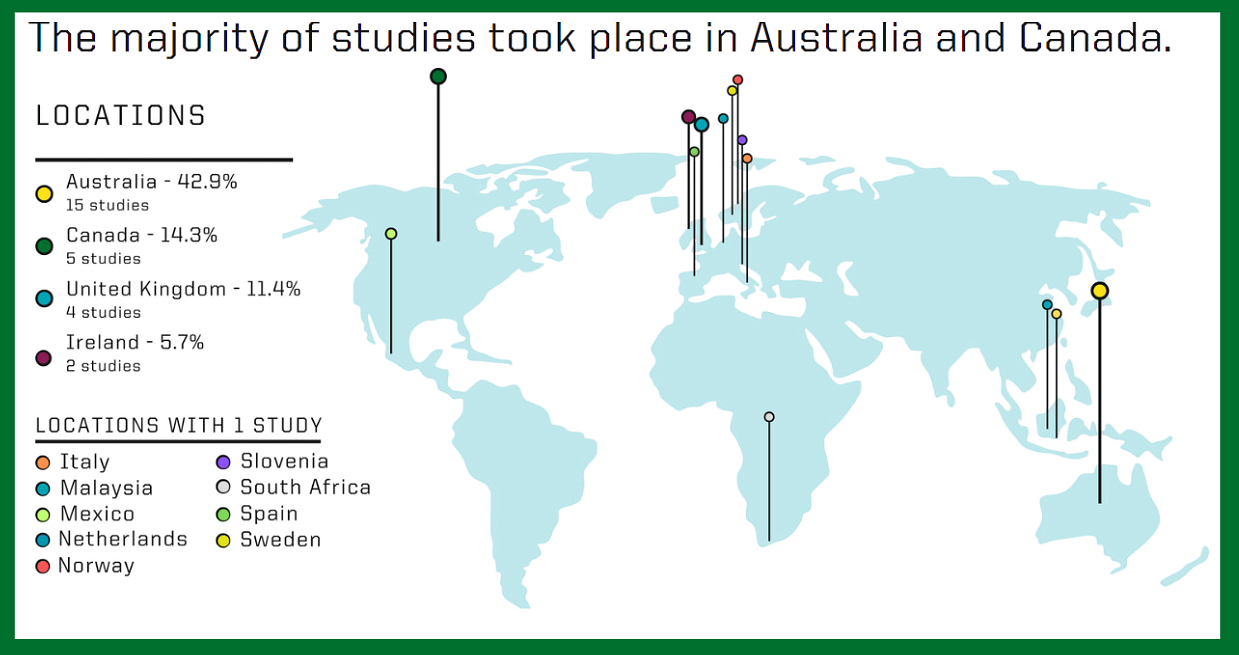

Our team reviewed studies on school-based prevention programs that were specifically targeted toward anxiety. By school-based, we mean programs that were delivered to students during the school day. Most of the studies we looked at were conducted in primary school settings, and around half of programs were delivered by teachers. One surprising finding was that none of the studies took place in the United States. Instead, nearly 43% of studies took place in Australia, followed by Canada (14%) and the United Kingdon or Ireland (almost 17%).

Why were there no U.S. studies?

What does this mean when interpreting our findings? First, it is important to note that there could be studies conducted in the United States that didn’t meet our inclusion criteria. It could also be that there are studies in the United States that involve prevention programs that target anxiety, along with other mental health disorders or other co-occurring risk behaviors, for example, substance use or delinquency. In fact, we heard from an educational stakeholder that schools in the United States often prefer to implement either health promotion more broadly or to deliver programs that simultaneously address multiple mental health challenges. In short, the lack of U.S.-based studies in our review could reflect a broader trend toward integrated mental health prevention efforts within American schools. Since our study only included programs primarily focused on anxiety, it wouldn’t include these types of programs.

Another consideration is the way that school systems and settings vary from country to country. Differences in policies, funding priorities, and standard “as usual” programming for health classes and prevention might explain the different uptake of anxiety-targeted prevention programs internationally. For example, in Australia where most included studies were conducted, the Australian National Children’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy has specific objectives related to schools, including that schools provide mental health promotion services, have adequate mental health professional support, and use evidence-based mental health programs. Despite the school setting differences, it is possible that anxiety prevention programs if delivered in U.S. schools, may have similar or even larger effects relative to the effects observed in international school settings.

To really understand how these programs would work in the U.S., we need more research in U.S. school settings with full reporting on the comparison conditions or school curriculums.

Do Anxiety Prevention Programs Work Better for Certain Students or in Specific School Settings?

Our team investigated whether anxiety prevention programs worked better for specific student populations and in different school settings. We did not find any evidence that anxiety symptom outcomes varied based on the factors we explored, like school level (primary or secondary), type of school (public or private), country where the study was conducted, or a study’s risk of bias. It is important to note that we weren’t able to investigate how these programs worked for students of different racial and ethnic backgrounds because around 86% of the studies didn’t report that information.

In sum, our review underscores the critical importance of addressing anxiety in childhood. While we found that school-based prevention programs can reduce anxiety and depression symptoms, the effects are quite modest. Findings show that significantly more work is needed to understand how these programs operate in U.S. school settings and the student populations for whom they work best.

HEDCO Institute Blog 12- June 26, 2024